Were the 'black peril' panics driven more by race or sex?

- Carla Norman

- Jun 15, 2020

- 7 min read

Module: HST4605 Race and the Desire for Difference

By: Carla Norman

‘Black peril’ panics have been described as a “hysterical obsession” as well as a “manufactured phenomenon”[1], yet there was very little evidence for these alleged crimes against white women. ‘White peril’ was much more common, yet it did not become a public fear. The ideology of settler colonialism in the African colonies of the British Empire allowed theories around the black race and sex, to thrive in the press and thus created stories of more frequent ‘black peril’ panics. The colonial fears of miscegenation and mixed-race offspring created a racial driving force, whereas the Victorian age created many fears around sexuality. However, in many cases theories surrounding both race and sex can be combined to create a stronger argument. Although there are arguments for sex and race each being the driving factors of the ‘Black peril’ panics, it is more convincing to argue that both race and sex were the driving forces behind the panics. This essay will discuss racial and sexual factors, and finally why these factors combined is ultimately what drove and enabled the ‘Black peril’ panics to reach such a scale across Africa in the late nineteenth and early twentieth-century.

Firstly, there are many racial arguments behind the ‘black peril’ panics. The white colonisers believed that they were civilised and the indigenous black people were savages. The Europeans thought that they had the moral high ground, as they were “‘civilising’, the ‘uplifting’ of ‘savages’”.[2] This was also reflected in their racialised class differentiations which involved ‘scientific’ theories such as craniology. This suggested that the physical differences of the indigenous peoples resembled apes, which contrasted to European faces.[3] This reinforced the idea that delicate white women must be protected from these less advanced people. The ideology of settler colonialism had a goal of replacing the indigenous peoples which involved expansion and elimination. The ‘black peril’ panics have been described as “a discourse of power capable of coding anticolonial struggle as the violation of women”[4], which suggests that these allegations of abuse and rape by black men on white women could give more of a reason as to why the indigenous peoples needed to be eliminated.

An important reason why the ‘black peril’ panics can be seen to be driven more by race is the lack of evidence for these alleged crimes. Etherington states that in the Natal colony in South Africa, very few cases had enough evidence to satisfy the judges and the juries, despite the high level of public alarm from the media.[5] The level and frequency at which these ‘black peril’ panics occurred were fabricated in the media to create public panic, and could be presented as a warning to white women as the colonialists would not have wanted them to mix with the black men, as they were viewed as a threat both racially and sexually. Fanon describes the black man as “the biological danger”.[6] Black men were viewed as a force which could threaten the English white race, as Anderson also argues that “degeneration was symbolic of the threat to ‘healthy British manhood’”.[7] ‘Black peril’ panics were driven by race through the colonial fear of the threat that indigenous and particularly black men could pose to Western society, especially from the idea that racial mixing would lead to racial impurities.

There are many reasons why the ‘black peril’ panics were driven by sex. The Victorian view of sex valued sexual restraint, as this was a sign of cleanliness and purity. Sexually transmitted infections were a “nightmarish spectre”, where the victims were turned into delinquents and deviants by white societal values.[8] Black men and women in the colonies were associated with an uncontrollable level of sexuality. Young states that “sex is at the very heart of racism”.[9] Black men were targeted in ‘black peril’ panics as they were seen as being overpowering and threatening towards white women. The “n****’s lustful bestiality”[10] suggests that black men have no control over their instincts and due to this public fear was able to be created, and the media was showing these men to have animal-like traits.

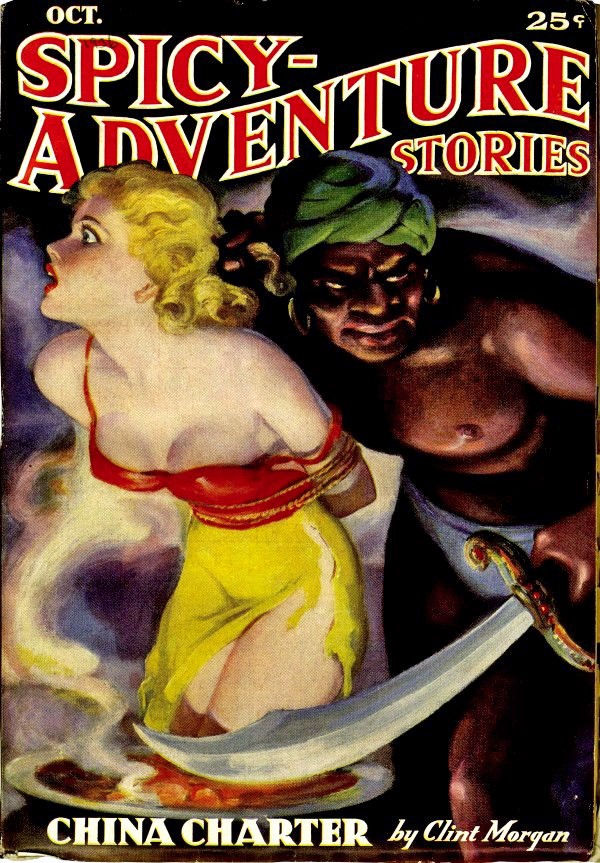

‘Black peril’ panics were driven by sex due to the white Western view that black men and women were sexually desirable. Young states that the sexual aspect was about the desirability of the ‘other’, which led to the idea of ‘blackness’ becoming a fanatic image.[11] An example of this is the cover of Spicy Adventure Stories.

This cover presents the black man as the villain, with an evil look on his face. He is also illustrated as wearing very little clothing, which implies that he is ‘primitive’ and ‘savage’. He is holding a sword which reinforces this danger. The white woman is illustrated with most of her clothing being torn off, which shows a sexual threat. The woman is also shown with a scared expression on her face, as if she is waiting to be saved. The ‘black peril’ panics were driven by sex through this popular image of the black man as having uncontrollable sexual urges, particularly targeting white women.

This led to a fear among white men that black men would steal white women away from them. For example, in colonial Zimbabwe, the settler society was overwhelmingly male, as white women were not allowed in the colony for the first two years.[12] ‘White perils’ became frequent where white men would abuse black women. However, there were many laws that protected white men so that while ‘black perils’ caused public outrage, ‘white perils’ were kept from the public eye. The Immorality Act of 1927 allowed miscegenation through matrimony, which meant that the white men could marry the black women with no consequences for having mixed race offspring.[13] Controlling the sexuality of black men was a key aspect of maintaining colonial rule, as “unrestrained sexuality was an unending threat to empire”.[14] Overall, the threat of sexuality was a major driving force behind the ‘black peril’ panics.

The most convincing argument for the driving force of the ‘black peril’ panics is a combination of both race and sex. Levine states that in order to understand the readings of sexuality to judge a society’s moral character, understanding racial difference was fundamental.[15] Race and sexuality are closely linked, especially in the colonial societies in Africa. There was a sense of “settler superiority”, which involved the white men being urged to guard against the polluting influence of black sexuality.[16] This shows that the ‘black peril’ panics were exaggerated because this reflected the attitudes of society towards the threat of black race and sexuality. It has also been argued that “concubinage in no way disrupted the existing racial or sexual power base”[17], but, sexual relations between a white woman and a black man were turned into a wave of fear and panic. The ‘black peril’ panics would not have become the “manufactured phenomenon”[18] that they did without both racial and sexual aspects.

Fanon in Black Skin, White Masks argues that when looking at the racial situation psychoanalytically, “in that of the Negro, one thinks of sex”.[19] Racial stereotypes in society were an essential driving force in the ‘black peril’ panics, and these stereotypes often involved ideas around sexuality. Stereotypes are “essentialising tropes of difference”[20], and for white colonisers, stereotypes were a way of differentiating indigenous peoples based on race and sex. O’Donnell argues that the rise of colonial rape rumours “both corresponded with and increased Western women’s colonisation and subsequent settler anxiety of miscegenation”.[21] This suggests that the idea of ‘black peril’ was used to warn women when they arrived in the African colonies to prevent racial mixing. These fears could be in order to uphold the “complex dynamics” of the order of society in the colonies.[22] There were fears over the racial aspect of black people in colonial society, as they were to always be at the bottom and repressed, due to believed physical and mental differences. There were also sexual fears to be considered, such as their perceived unrestrainable sexual desires.

In conclusion, when discussing the driving forces of ‘black peril’ panics, it cannot solely be due to either race or sex. Both racial and sexual aspects work together to challenge social hierarchies in the colonies, but also these aspects were used to reinforce the societal structure. With the aid of the media, ‘black peril’ panics were able to become a global phenomenon, even with the lack of real evidence, due to these stereotypical beliefs and fear that the indigenous African peoples would gain growing economic and political power. The ‘black peril’ became a tool for colonial society, to the extent where it was no longer about rape or sexual abuse. The colonial world allowed ‘black peril’ panics to become a global concern, but this concern was shared by Western ideas surrounding both race and sex.

Footnotes

[1] J. Pape, ‘Black and White: The ‘Perils of Sex’ in Colonial Zimbabwe’, Journal of Southern African Studies, 16:4 (Dec., 1990) p. 699

[2] N. Etherington, ‘Natal’s Black Rape Scare of the 1870s’, Journal of Southern African Studies, 15:1, (Oct., 1988) p. 43

[3] R. J. C. Young, Colonial Desire: Hybridity in Theory, Culture and Race (London: Routledge, 1995), pp. 90-91

[4] J. Sharpe, Allegories of Empire: the Figure of Woman in the Colonial Text (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1993) p. 130

[5] Etherington, ‘Natal’s Black Rape Scare’ p. 37

[6] F. Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks (London: Pluto, 1986) p. 127

[7] D. M. Anderson, ‘Sexual Threat and Settler Society: “Black Perils” in Kenya, c. 1907-30’ The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, 38:1 (2010) p. 48

[8] Anderson, ‘Sexual Threat and Settler Society’ p. 47

[9] Young, Colonial Desire, p. 91

[10] Sharpe, Allegories of Empire, p. 128

[11] Young, Colonial Desire, p. 91

[12] Pape, ‘Black and White’ p. 701

[13] G. Cornwell, ‘George Webb Hardy's The Black Peril and the Social Meaning of 'Black Peril' in Early Twentieth-Century South Africa.’ Journal of Southern African Studies, 22:3 (1996) p. 443

[14] P. Levine (ed.), Gender and Empire, (Oxford: OUP, 2004) pp. 134-135

[15] Levine, Gender and Empire p. 136

[16] Anderson, ‘Sexual Threat and Settler Society’ p. 48

[17] Levine, Gender and Empire, p. 140

[18] Pape, ‘Black and White’ p. 699

[19] Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks, p. 123

[20] Sharpe, Allegories of Empire, p. 127

[21] K. O’Donnell, ‘Poisonous women: Sexual Danger, Illicit Violence, and Domestic Work in German South Africa, 1904-1915’, Journal of Women’s History, 11:3 (1999) p. 32

[22] Pape, ‘Black and White’ p. 702

Bibliography

· Anderson, David M. ‘Sexual Threat and Settler Society: “Black Perils” in Kenya, c. 1907-30’ The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, 38:1 (2010)

· Cornwell, Gareth. ‘George Webb Hardy's The Black Peril and the Social Meaning of 'Black Peril' in Early Twentieth-Century South Africa.’ Journal of Southern African Studies, 22:3 (1996)

· Etherington, Norman. ‘Natal’s Black Rape Scare of the 1870s’, Journal of Southern African Studies, 15:1, (Oct., 1988)

· Fanon, Frantz. Black Skin, White Masks (London: Pluto, 1986)

· Levine, Phillipa (ed.) Gender and Empire, (Oxford: OUP, 2004)

· O’Donnell, Krista. ‘Poisonous women: Sexual Danger, Illicit Violence, and Domestic Work in German South Africa, 1904-1915’, Journal of Women’s History, 11:3 (1999)

· Pape, John. ‘Black and White: The ‘Perils of Sex’ in Colonial Zimbabwe’, Journal of Southern African Studies, 16:4 (Dec., 1990)

· Sharpe, Jenny. Allegories of Empire: the Figure of Woman in the Colonial Text (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1993)

· Young, Robert J. C. Colonial Desire: Hybridity in Theory, Culture and Race (London: Routledge, 1995)

Primary Source

· Cover of Spicy Adventure Stories, October 1936

Comments